Hanaa Malallah | She/He Has No Picture

Wednesday 31st March 2021

-Friday 30th April 2021

Online Only

SHE/HE HAS NO PICTURE by HANAA MALALLAH

Curated by Joe Start

She/He Has No Picture is an online exhibition by Hanaa Malallah, resulting from her exploration of the relationship between the physical and virtual worlds, an important thread in her oeuvre. Malallah has explored the relationship between the visible/invisible and the mortal/immortal throughout her career, and this exhibition presents new digital work at these intersections. Developed conceptually and technically between 2019-2020, the digital work in She/He Has No Picture comprises a selection of machine-processed still and moving images that stem from and manipulate Malallah’s large scale physical work of the same name (first exhibited at MoMA PS1 in 2019-20).

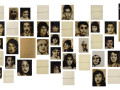

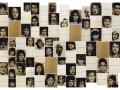

This online presentation (images viewed to the right) begins with a selection of generative artworks, moving images in GIF form and stills in jpg (the Invisible Portraits), followed by images of Malallah’s large-scale physical work and details. The physical work documents and commemorates the victims of the Amiriyah shelter bombing (February 1991), some of whom are represented by images, some for whom photographic portraits did not exist. When realising the physical work, Malallah rendered her portraits in her unique soft sculptural technique, using only canvas – burnt to varying degrees – to achieve tone, while representing the physical process of destruction. Where photographs did not exist, the victims are commemorated only with the words “She” or “He has no picture”, or their names, written in the written in the Abjad Code ‘alphabet’ (حِسَاب ٱلْجُمَّل).

The digital work takes this a step further, harnessing the computer’s ability to visually generate images that are simultaneously lifelike and ghostly. These works have been created by training a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) – an algorithmic architecture – on a dataset of Malallah’s artworks, producing an entirely new range of portraits, that captures elements which the human mind cannot conjure alone. As part of this exhibition, a selection of works will be minted as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) on the Tezos-based platform Hic et Nunc. These NFTs will be released over the duration of the exhibition and can be collected by clicking here. (For a guide on how to collect NFTs on Hic et Nunc, please click here, or contact us through email, Twitter or Instagram.)

The following text was written by Christa Paula, based on research and conversations with Hanaa Malallah. London, July 2019:

She/He Has No Picture (2019) is a wall installation commemorating the victims of the pre-dawn bombing of Public Shelter Nr. 25 in the Al Amiriyah neighbourhood of Baghdad on the 13th of February 1991. Without warning, two American F-117 planes each fired a laser-guided ’smart’ missile, instantly incinerating over 400 people – mostly women, children and old men. Shortly afterwards, a small booklet was published listing the victims names. Only 100 of those were accompanied by a photographic portrait. The others merely had a notice printed beside their names reading either ‘She has no picture (female)’ or ‘He has no picture (male).’

Two or three months after the event a friend and I went to visit the ruined shelter. It was dark, only dimly lit by the hole made by the missiles in the ceiling. A toxic smell of smoke and charred bodies permeated the air. Human remains fused into the very fabric of the interior by the intense heat of the explosions and an uncanny panorama of scorch marks on walls and ceiling had created a horrific yet mesmerising visual spectacle. Families had hung photographs of their loved ones and arranged some candles, creating makeshift shrines of remembrance and grief. People were praying, others crying. Some, like us, were simply silenced in shock and disbelief. The artist in me desired to take photographs but, during that pre-smart-phone time, in Iraq we were living under sanctions and film was almost impossible to come by. There was no need. The images etched themselves deeply into my heart and, a strong desire to memorialise the dead of Al Amiriyah took up residence in my soul.

Over the years, a file was accumulated. With the advent of the internet, related content increased and continues to grow with every annual commemoration and my files are now stored in the Cloud. Names of victims, pictures, observations, comments and condemnations; even the small booklet of victims I had once owned but lost is there. The shelter can be visited in virtual reality on YouTube: steel rods bent like willow switches, crazed slabs of concrete, scorched matter of many hues. Viewing it on my laptop in London viscerally yanked me back to 1991 and propelled me into the studio. Using burnt fabric on a small canvas, I started to build the face of a female victim whose image I had downloaded from the internet.

Artists sometimes say about a particular artwork that it was simply channelled through them. I understand this now. 28 years after visiting the shelter and its horrors I was suddenly ready. The material practice which I have termed ‘Ruins Technique,’ where the creative process begins with an act of destruction, has matured over the span of three decades. There is both an expansion and a synthesis of processes in this project; a revisiting of my love for portraiture, numbers and equivalents, secrets and codes, the virtual and the actual. Relationships between concept, media, techniques and content work with rhizomatic fluidity. In the end, however, this is an ethical endeavour and, hopefully, a restorative one.

Central to this project is the face: the face of victims, of viewers and of the faceless and its relevance to memory and mourning. I question the forms and physicality of the representation of the face and what it means in the era of the internet not to have one. The role of the human face is paramount in the social and mutually responsible encounter with the Other. It is the locus of person-hood and is capable of expressing meaning before a single word is spoken. It simultaneously conveys resistance and defencelessness and its presence forbids us to kill. After all. “Thou shalt not kill” is a moral imperative intrinsic to all religions.

In its fully assembled form ‘She/He Has No Picture’ (2019) is an expanded media wall installation with five constituents:

1. Bas-relief Portraits: 408 human beings were incinerated on the 13th of February 1991. Of these only 100 people had their picture reproduced in the booklet printed not long after the incident. I sourced their faces from the internet and worked off copied screenshots. These were often murky, indistinct and flat. Each portrait was then built up layer upon layer into bas-reliefs with burnt or singed calico, thin cotton material with the texture of bandages. At times it felt I was working with clay or flesh – burning flesh. At other times it suggested painting. Raised from the flat surface of the canvas the faces assumed the illusion of three-dimensionality emerging through the material, frozen in the penultimate moment before death. Their eyes seemed to follow me around the studio, gazes imbued with foreknowledge of an imminent and harrowing fate. A death gaze! As though time had collapsed between the moment in life when the original photograph was taken, the actual moment of death, and that moment long after death when I sourced their image from the internet.

2. Brass-Plaques: Between the bas-relief portraits are installed six highly polished brass plates capable of mirroring the viewers faces. A sentence written in Arabic is engraved on each surface reading either She has no Image or He has no Image, unintelligible to the non-Arabic reader. These were cut into the brass with a laser, referencing the technology that helped deliver with precision the fatal bombs and consequently the deaths of those seeking refuge in the shelter. Although this face-to-face confrontation of the viewer with her/himself may be an act of visual substitution, an ethical appeal to our common humanity and vulnerability, it is fleeting and does not, cannot, restore the likeness of any of the remaining 308 victims.

3. Personal Numbers: The booklet listing the names, gender, age, occupation, and former address of the victims leaves 308 spaces blank. They have no picture and consequently, they have no face – no personality. Like ghosts, they are neither self nor other. They have been abstracted, enumerated, rendered a statistic or code. Ethical conduct, mourning, or reparation are thus compromised.

Here the missing picture has been replaced by a small, plain portrait-sized canvas depicting the number equivalents of the 308 victims names. Numbers, from the first Mesopotamian signs/numbers to the Abjad system where each letter of the Arabic alphabet is assigned numerical value, have been crucial to my practice for a long time. It is a simple form of encryption, rendering legible information into a secret which requires a key to decode. It has been used in magic and numerology and variations of it exist in many ancient cultures around the globe. I have always been intrigued by archival numbers painted onto objects in museums and I have had the number equivalent of my name tattooed onto my left forearm. It reads 5.50.1.1.40.1.30.1.30.30.5. Note that I have just revealed a part of the key to crack the code of the victims’ names and their gender.

4. Digitally Reconstructed Portraits: I have been contemplating the ever diminishing gap between human consciousness and artificial intelligence for some time and, in the course of sourcing the portraits of the 100 victims with pictures for the bas-reliefs, I realised its creative potential for the fourth part of this project. By coding and feeding the available information of victims without a picture into a computer program, digital portraits may be (re)constructed with the aid of suitable algorithms. We will never know if the resulting image approaches the likeness of the long-deceased, but there will be a virtual human face carrying a name, gender, age, occupation, status and place of residence. An identity. These disembodied avatars were conceived to realise an online presence.

5. Memorial Wall: The comprehensive list of the names of victims is to be reproduced in large scale on the wall of the exhibition space to create a temporary site for mourning. The names and details of each person killed by the American ‘smart’ bombs were originally listed in the attendance ledger of the Al Amiriyah Public Shelter Nr. 25 for the night of the 12th to to the 13th of February. The ledger survived. It was reprinted in the previously mentioned small booklet I found again on the internet.

Memorials, being public sites for aesthetic engagement, are of profound social and political relevance. Although the largest single documented incident of ‘collateral damage’ in the history of modern warfare since WWII, outside of Iraq this tragedy has all but faded from memory. Few know that, two days before the bombing, the Al Amiriyah Public Shelter Nr. 25 was taken off the protected list when the Pentagon received intelligence that alleged the building’s re-purposing from civilian refuge to a military command centre. There was no warning about its change in status. Journalists visiting the shelter in the immediate aftermath found no evidence of military presence. Shortly after, the US military curtailed its bombing sorties of urban neighborhoods.